By Jen McConnel and Pamela Beach

When we first set out to explore secondary teachers’ beliefs about teaching writing in Canada and the United States, our classrooms looked drastically different than the classrooms of 2020. The teachers who shared their insights and struggles with us were teaching face-to-face, using technology as it fit their pedagogical styles and their students’ needs, and collaborating in person with colleagues throughout the year. As the 2020 school year came to a close, we all found ourselves teaching online in various iterations of emergency remote learning, and many of the things that we took for granted before, like the ability to bounce ideas off a colleague over lunch, are no longer things we can expect in the near future. And yet, the insights of the teachers who participated in our study can still offer guidance as we reconsider the ways in which we will approach writing instruction in classrooms this fall, and beyond.

Frank, one of the teachers we spoke with (all names are pseudonyms), offered a way of looking at teaching that strikes us as particularly useful as we begin reconsidering what our classes will look like in the fall: “Good teachers are highly reflective, which is similar to the writing process. You have to be kind of ruthlessly revisionist, so the more I reflect on my teaching, it just gives me better ideas, and that’s where most of my writing comes from: what I’m doing in the classroom.” Perhaps we will emerge from the pandemic with a stronger sense of ourselves and the role writing will play in our teaching. But just as the strengths that we drew on in our pre-pandemic classrooms will help us re-envision what it means to teach writing in the fall, the frustrations we have experienced will continue to shape our practice. As Sue, an Advanced Placement teacher in New York shared with us, “Teaching writing has really been these little hit and miss things that I’ve found along the way. There was a long time I felt like I’d missed the memo. I was alone in my room.”

In this post, we hope to connect teachers by sharing how teachers across Canada and the United States approach writing instruction and develop confidence. Based on our pre-pandemic conversations with these teachers, we offer a framework for teachers and students to co-create their own confident writing classrooms.

In the study that informs our framework, we sought to explore the aspects of writing instruction that high school teachers approach with confidence, and to consider the ways in which that confidence transcends the bounds of culture or curriculum. When we speak of teacher confidence, we are referring to teachers’ self-reported sense of their ability to do certain tasks related to writing instruction, as well as to teachers’ responses to interview questions such as, “how confident are you that you can teach writing effectively?”

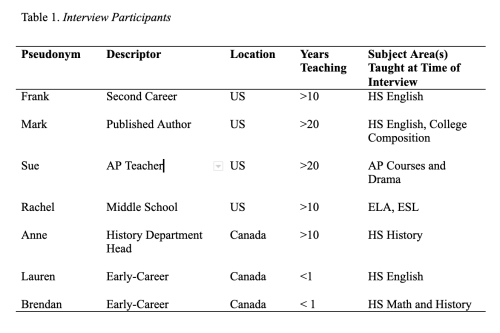

The 60 teachers who completed the Teacher of Writing Self-Efficacy Scale (TWSES, Locke and Johnston, used with permission) were then invited to participate in one-on-one interviews: 7 were available to be interviewed (Table 1). Half of the teachers we interviewed were currently teaching in an ELA context, while the others were teaching within the humanities, reinforcing the reality that teachers are already aware of: writing happens in classrooms of all disciplines, but policy conversations often focus attention on the work of ELA teachers to provide writing instruction. However, writing is happening across contexts, and teachers beyond the ELA classroom have a great deal of insight to share into their writing pedagogy.

Based on the themes that emerged from this study, we propose three overlapping facets of writing instruction that teachers can focus on in order to increase confidence with writing for both teachers and students: context, authority, and identity (Figure 1). These facets may be approached in any order, but we suggest teachers start with the area they feel most confident with.

The Context of Writing. One possible entry point for teachers might be the context of assigned writing. Context matters a great deal in individual writing work, but it is also a vital component to building an authentic writing community where all voices are honored. And, as Mark reminded us, context is not just about the type of writing, but the process as well: “The reason I believe in revision is that’s how the real world works. When an editor sends something back to you, it’s not because they hate it, it’s because they saw something that you didn’t see that needs to be corrected.” As we reconsider the changing shape of our classrooms in the fall, it would also be helpful to think about the ways in which everyone’s context has shifted dramatically. If there ever was any question about deliberately integrating out of school literacy practices into our teaching, the fact that our classrooms are no longer bounded by walls or school building makes it imperative that we create writing opportunities for students that allow them to express the complex contexts of their lives. MC Walker offers some starting points to consider what authentic writing looks like in our current reality.

The authority of a writer. Next, teachers might focus on authority in texts and authority in the writing community, where all members work to co-create and strengthen their individual and collective understandings of what it means to write with authority. Developing a sense of authority of a writer includes understanding the skills, styles, and content that are appropriate to any given task, and choosing between the various tools of the writer’s toolbox in order to approach the task from a place of ownership and confidence. Lauren offered some suggestions during our interview to help students claim this ownership when she reminded us, “There are so many different aspects of writing that you don’t necessarily consider yourself a writer until you think about it, but then you realize it’s very much a part of your daily life.” Teachers can invite students to explore the idea of authority individually and as a classroom community, and build assignments from that shared understanding of what it means to write with authority, which is tied to the next aspect of the framework.

The identity of a writer. During our interview, Rachel lit up when we asked her the best part of teaching writing. “You always find those couple kids who figure out their voice, who find their voice on the page…When that happens, that’s not just words on a page, it was a huge part of their identities as young people and what they will be when they become adults.” Students might begin by exploring the ways in which identity is enacted and developed through writing. Offering culturally responsive writing prompts that make space for student individuality is one way to cultivate a writing classroom that values students’ identities and helps them see themselves as writers engaged in authentic, important writing, as suggested by Kristen Storm in this post.

The potential of this framework is creative, offering teachers (and students) multiple ways into a conversation about writing that will not only enhance confidence, but will create a classroom culture in which diverse writing strategies and perspectives are valued. Our framework is one way to encourage students to engage more deeply with their own writing practices in any context, and we are both considering ways to integrate this framework into our teaching in the fall.

How can you co-create a confident writing classroom with your students and colleagues?

- Play to your strengths. There are likely aspects of writing instruction that you are more confident with than others. Do you thrive in helping students establish writer’s workshop procedures, or are you at your best when it comes to the mechanics of polished writing? Are you a whiz at collaborative technology in the writing classroom to facilitate peer review? Embrace that strength, but also don’t be shy of reaching out to professional colleagues within and beyond your district (and discipline!) to seek guidance as you develop your low-confidence areas.

- Foster an authentic context for writing. One way to help students feel authenticity and ownership of their writing tasks is to ask them what matters to them. Do you have a group committed to social justice? Consider allowing students to draft emails to politicians and online petitions to advocate for their causes. Are your students focused on university and college admissions? Spend time practicing application essay writing, and help students hone the craft of concise, passionate communication.

- Create a community of writers. Take the lead by modeling a writer identity to your students, and invite them to take ownership of their own writing identities, too. Start each synchronous class with low-stakes writing activities, like a free-write or daily journal, and write right along with your students. When you assign a major writing project, offer your own exemplars of various stages in the process. Do you have colleagues who are interested in expanding their writing identities? Consider starting a staff writing group, and be transparent with your students about the process. Writing does not have to be a solitary endeavor!

Learning to write and learning to teach writing cannot be distilled into an overly simple set of instructions. A myriad of factors is at play throughout a teacher’s career, and there is no “one size fits all” way to become a teacher of writing. However, we can work to co-create confident writing communities if we focus on context, authority, and identity in our writing and our classrooms. In the coming school year these constructs will likely become even more crucial: whether we are teaching online or face-to-face in the fall, our students’ experiences since March will have likely transformed them and left deep imprints. In a writing classroom that values student authority and offers multiple contexts for writing, perhaps we can help our students (and ourselves) make sense of our shifting collective and individual identities.

Jen McConnel is currently an Assistant Professor of English Education at Longwood University. A long-time educator, her research aims to support teachers and students as they write across contexts.

Pamela Beach is currently an Assistant Professor in Language and Literacy at the Faculty of Education, Queen’s University. Her background as an elementary teacher has influenced her research which centers on the dissemination of research-informed literacy practices.

Peer reviewed through the Writers Who Care blind peer-review process.

References

Lea, Mary R., and Brian V. Street. ‘The “Academic Literacies” Model: Theory and Applications’. Theory Into Practice, vol. 45, no. 4, 2006, pp. 368–77.

Locke, Terry. Developing Writing Teachers: Practical Ways for Teacher-Writers to Transform Their Classroom Practice. Routledge, 2015.

Locke, Terry, and Michael Johnston. ‘Developing an Individual and Collective Self-Efficacy Scale for the Teaching of Writing in High Schools’. Assessing Writing, vol. 28, 2016, pp. 1–14, doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.asw.2016.01.001 1075-2935/.

Strom, Kristen R. “Embracing Student Voice and Agency in a Composition Curriculum.” Writers Who Care. January 13, 2020. https://writerswhocare.wordpress.com/2020/01/13/embracing-student-voice-and-agency-in-a-composition-curriculum/

Walker, M.C. “Writing Our Way Through: What Teaching During COVID-19 Can Teach Us About the Power of Authentic Writing.” Writers Who Care. July 6, 2020. https://writerswhocare.wordpress.com/2020/07/06/writing-our-way-through-what-teaching-during-covid-19-can-teach-us-about-the-power-of-authentic-writing/